Writers Make History on the Picket Lines

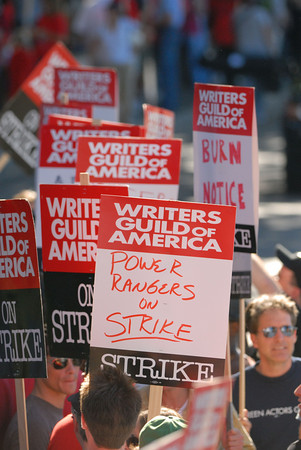

Galvanized by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers' refusal to bargain fairly members of the Writers Guild of America, West and Writers Guild of America, East refused to go to work and staged the largest action in the Guild's 74-year history.

On Monday, November 5 at 12:01 a.m, more than 3,000 WGAW members walked picket lines throughout the day at 14 locations and demanded that the Companies bargain fairly with writers. By Tuesday, the number had swelled to 3,200.

“The level of support is fantastic not only within the Guild but with the general public,” said former Simpsons showrunner Mike Scully. “We've never had more leverage than we have right now.”

“We've had more support than I could have imagined,” added TV writer Jamie Rhonheimer. “Everybody is in this for the long haul.”

Joe Medeiros, head writer for The Tonight Show with Jay Leno and a member since 1989, said he had never seen the membership as unified as it is now. For Medieros, the historic turnout spoke to the significance and urgency of these negotiations and the issue of New Media, in particular.

“I see the handwriting on the wall,” said Medieros about New Media. “That's the way television's going. That's how my kids watch stuff. They're downloading it, they're watching it on their computers, and the writers aren't being paid for that. If we don't do something now, we're gonna be out of business.”

Writers made it clear that this fight was not only for themselves but for those who will follow them. “I'm so terrified for the next generation of writers to come that their residuals will be diminished or taken away entirely once we make the move to computers,” said Desperate Housewives' Marc Cherry. “That's why this strike is so important. We're fighting for our fair share of the New Media business, and if we don't get it now, we may all be screwed in the future.”

“People who fought this fight before us have made sure that guys who only work half the time get enough residuals to live,” said Medieros. “That's why we're fighting this fight for the writers of the future. We can't leave them out in the cold when it comes to what's going to happen five, 10 years from now with the Internet.”

Writers are winning over the public

Study shows people side with scribes

By DAVE MCNARY

There's an image war raging during the WGA strike, and the writers seem to be winning.Public sympathy sides with the scribes, as a study, released Wednesday, indicates.

And during the past few weeks, mainstream media outlets have devoted significant coverage to the strike in news stories and op-ed pieces. Slate's Jack Shafer noted Tuesday that such coverage has been generally sympathetic.

It certainly helps the writers that the companies with which they are at war have CEOs that have to talk out of both sides of their mouths. On the one hand, they have to claim everything is financially rosy so shareholders are happy. That includes profit forecasts from downloads and other digital platforms. Problem is, when it comes to the strike, that's the very area which they claim isn't monetizable at all.

But while writers may be enjoying their public standing, IATSE topper Thomas Short is swiping away, claiming that a strike was always pre-set.

"It's time to put egos aside and recognize how crucial it is to get everyone back to work, before there is irreversible damage from which this industry can never recover," Short said in a letter to WGA West's Patric Verrone.

The WGA trumpeted a pair of surveys Wednesday showing plenty of public sympathy with backing of 69% in a Pepperdine poll and 63% in a SurveyUSA poll, while the companies received a only a smattering of support with 4% and 8%, respectively.

And the announcement came on the same day that WGA West prexy Patric Verrone and SAG topper Alan Rosenberg huddled with multiple elected officials in Washington, D.C., to explain the guilds' position.

"These polls prove that the public understands what's at stake here," Verrone said in a statement. "Our fight represents the fight for all American workers for a fair deal."

The news release also included a strong endorsement of the WGA's position by a labor economist at Pepperdine, which conducted the survey. "Public sentiment plus the economic disruption that the strike has caused can serve as powerful leverage and bodes well for writers in ongoing negotiations," said David Smith.

As for talks, no new ones are scheduled. In what could be a positive development, AMPTP chief Nick Counter has dropped the condition that the guild has to stop the strike for a few days for negotiations to resume.

In response to Short's letter, Verrone said: "Our fight should be your fight," and noted that "for every four cents writers receive in theaterical residuals, directors receive four cents, actors receive 12 cents and the members of your union receive 20 cents in contributions to their health fund."

The WGA's repeatedly referred to four cents as the usual residual writers receive per DVD sale. On the last day of contract talks, guild negotiators took the DVD proposal -- seeking to double that rate -- off the table but were infuriated by what they saw as a lack of movement by the companies and have hinted since then that it might be back on the table. The WGA had no comment Wednesday about the status of its DVD proposal.

Lack of progress in getting both sides back to the table, has led to the expectation that the Directors Guild of America will launch its negotiations soon — during what would be the typical window for DGA talks of at least six months before the June 30 expiration.

But the situation's so fluid that speculation's ruling the day, such as an "interim strike" scenario in which the WGA would go back to work at some point in the next few months -- and then go back on strike if talks don't lead to a favorable deal.

Short shots

Short noted in his letter to Verrone that more than 50 TV series have been shut down by the strike.

"More will come," he added. "Thousands are losing their jobs every day. The IATSE alone has over 50,000 members working in motion picture, television and broadcasting and tens of thousands more are losing jobs in related fields."

The IATSE topper noted that he took issue late last year with Verrone over the WGA's defense of its strategy in delaying contract talks with studios and nets until the summer.

"When I phoned you on Nov. 28, 2006, to ask you to reconsider the timing of negotiations, you refused," Short said. "It now seems that you were intending that there be a strike no matter what you were offered, or what conditions the industry faced when your contract expired at the end of October."

Short also took aim at recent comments by WGA West exec director David Young, in which the exec said he would not apologize for the strike's economic impact.

"This is hardly the point of view of a responsible labor leader, someone dedicated to the preservation of an industry that has supported the economies of several major cities for decades," he added.

SAG's Rosenberg said Wednesday he decided to join Verrone in Washington D.C., because the Screen Actors Guild will be facing the same issues next year. The SAG contract expires June 30.

"It's important to impress upon (Washington) that this isn't about wealthy actors or writers getting richer," Rosenberg added. "The average writer makes $60,000 a year, the average actor makes less. It's a question of keeping our heads above water with residual payments."

Verrone and Rosenberg met with Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.), Reps. Howard Berman (D-Calif.), Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), John Dingell (D-Mich.) and Edward Markey (D-Mass.). Dingell chairs the House Energy and Commerce Committee, and Markey is chairman of the Subcommittee on Telecommunications. At the FCC, they met with commissioners Michael Copps, Jonathan Adelstein and Robert McDowell.

Rosenberg and Verrone characterized the guilds as being at a disadvantage in trying to negotiate with seven multi-national conglomerates — noting that they all are supposedly competitors but negotiate together. "They're picking off the unions one at a time," Verrone said.

The WGA and supporters have also stayed on point during the past four months on the key issue of new media, in which bigwigs finding themselves infected with the mixed messaging bug.

On one hand CEOs of major media congloms are selling Wall Streeters on the fact that their digital offerings are growing like gangbusters and driving the bottom line. On the other hand, those same execs are holding out their hands and saying, a viable business model just doesn't exist and profits just aren't rolling in yet to give striking scribes what they want.

The problem is the congloms are stuck in the precarious position of angering shareholders: tell them that your company isn't growing and the stock plummets. Let the strike continue for six months or more and you anger those same shareholders, because in reality, companies will be losing revenue, as a result.

WGA supporters have compiled effective videos combining bullish pro-digital statements by moguls with the assertion that writers aren't getting anything.

So it's no surprise that company toppers are standing in the shadows and declining to state their case to an increasingly angry mob of writers. They just don't know what to say yet -- unless it's positive.

During the recent rounds of earnings reports, News Corp's Rupert Murdoch touted Fox Interactive Media as a strong profit generator, earning nearly $200 million in the past quarter alone, an 80% increase over last year, thanks to MySpace, Photobucket and other online properties.

Across town, Bob Iger said parts of 160 million TV episodes have been viewed on ABC.com, while 33 million downloads of the alphabet web's shows have been purchased on Apple's iTunes store. He estimated that the Mouse House's digital revenue will be about $750 million this year.

And NBC's Jeff Zucker said that the peacock made just $15 million in a year selling video on iTunes.

Oddly, those same toppers aren't pushing forward negative numbers to hold the WGA at bay — such as Forrester Research's prediction that growth of the paid download market will drop to 100% versus 200% next year; or that the sale of movies online will drop by 56% in 2008, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers.

When negotiations collapsed on Nov. 4, the AMPTP had offered to start paying for streaming video with a promotional window and had agreed to give the WGA exclusive jurisdiction on made-for-the-Internet writing on derivative works.

Disney pickets

The WGA has continued to picket more than a dozen locations in Los Angeles and staged a protest outside the World of Disney store on Fifth Avenue in New York on Wednesday, drawing more than 400 supporters.

A large, inflatable, cigar-chomping pig stood at Fifth and 55th Street outside the World of Disney store. Barricades ran the length of the block between 55th and 56th when it became clear that the picketers would not be contained to the sidewalk.

"I've had a lot of pedestrians telling me, ‘Hey, good luck with this,'" said "Late Show With David Letterman" scribe Steve Young. "I don't know if the approval of tourists is going to bring Les Moonves to his knees, but it makes us feel good."

Meanwhile, breaking a lengthy studio silence, ABC Studios has become the first arm of any conglom to respond individually to allegations made during the strike that it contends are inaccurate.

A Writers Guild of America East leaflet passed out Wednesday in front of Manhattan's World of Disney store quoted Disney's Bob Iger, who has said that the conglom generates $1.5 billion in digital revenue annually. The scribes, the WGAE claimed, earn nothing from that.

An ABC Studios spokesperson, who said she was tired of reading "distortion of information" by writers in newspaper articles and blog posts without any response from the producers, drafted this statement:

"The WGA leadership is deliberately distorting the facts. As the WGA knows full well, more than half of Disney's digital revenues are from sales of travel packages and the vast majority of the rest is from online advertising on sites like Disney.com and ESPN.com and through online merchandise sales. The WGA also knows its members have been paid residuals on entertainment content downloaded via iTunes. Deliberately misleading the public is not the best way to resolve this issue and get Hollywood back to work."

In response, the WGAE didn't disagree with Disney's account of where the $1.5 billion comes from, but did point out that the congloms have so far not been willing to open the books and prove how much money has been generated specifically from TV/film downloads and streaming:

"We would better know the nature of Disney's and ABC's revenues from digital if they would more fully and transparently reveal them to us. For example, their statement does not mention that much of the online advertising on their websites accompanies streaming video of our members' work in television and film for which they receive absolutely nothing. All we're asking for is a fair, respectful, small share."

Separately, a group of assistants is organizing a picket to support the WGA. Slated to take place Monday from 12-2 p.m. in front of the main gate of the Fox lot, organizers said the event is for below-the-line employees, "especially those who've lost their job due to the strike" to "show the media conglomerates that they need to take responsibility for their own decisions and not blame the writers for their layoffs."

1 comment:

FROM THE LATEST WORKERS’ CHARTER:

HOLLYWOOD WRITERS TO STRIKE

A Hollywood writers’ strike is underway.

The Writers Guild of America, the union representing film and television writers, has called its members out on strike to force studios and network heads to offer proper compensation for work appearing on DVDs and other new media outlets.

Production companies have been making billions at the writers’ expense. Trade magazine Variety noted, “For a moderately successful film selling 1 million DVDs and generating $15 million in wholesale revenues, the credited writers would split a payout of around $50,000—pretty tiny compared with the $10 million in profit the studio will see.”

Since writers originate projects that then take several weeks, if not months or years, to see the light of day, their strike will have a slow ripple effect on the entertainment industry—starting with the late-night chat shows and topical satire programs and slowly seeping through episodic television. Feature films won’t feel the pressure until the middle of next year.

Writers striking would include David E. Kelley of Boston Legal, Carol Mendelsohn and Naren Shankar of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, Krista Vernoff of Grey’s Anatomy, Rene Balcer of Law & Order, Greg Daniels of The Office, James L. Brooks, Matt Groening and Al Jean of The Simpsons and dozens of others.

Talk show host and comic David Letterman spoke out in defence of the writers, calling the producers “cowards, cutthroats and weasels.” His own show, along with other scripted talk shows, such as “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” and “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart,” are among those that will be first affected by a strike. The shows will be replaced by repeats.

Both the Screen Actors Guild and the Teamsters union, which represents drivers, location scouts and animal wranglers, among other industry workers, have announced their intention to respect WGA picket lines.

It is expected the New Zealand Writers’ Guild, which along with Australian, Canadian, British and Irish unions is affiliated in an International, will instruct all its members to decline any approaches from US production companies during the course of the dispute.

Given the intransigence of the two sides, the stoppage is unlikely to be brief. Much may depend on the actors’ and directors’ guilds, who share many of the writers’ grievances and whose contracts are up for renegotiation next June.

One scenario would have all three guilds on strike, at which point Hollywood would be forced to shutter its doors completely—a nightmare the producers and media owners are likely to try to counter with a divide-and-conquer strategy to pit the guilds against each other.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ALSO

BIT OF BACKGROUND HISTORY US WRITERS’ GUILD:

There was a cartoon in the New Yorker once showing a group of picketers walking around in a circle, the way they do in the United States to avoid being arrested for loitering. And all the picketers were carrying big placards. Except the placards were blank. And a passenger in a cab, curious, was peering at the picketers and the cab driver explained: “It’s a writers’ strike.”

In its sheer potency, a writers’ strike can be been compared only to a philosophers’ strike. Despite this, in this talk about the unionisation and radicalisation of Hollywood in the thirties and the reaction of the forties, I’ll largely be concentrating upon the writers because writing happens to be my job and because the second most-asked question of the infamous and fabulously named House Committee on Un-American Activities seemed to be, “Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Screen Writers’ Guild?”

It wasn’t just the sun that brought the movie industry to Los Angeles. LA was a non-union town. The “wide open west” was also known as the “wide open-shop west”.

As the curtain fell on the era of the silent movies and the 1930s began, the only unions in the movie industry were the small and quiet craft union, the Musicians’ Union, and the much bigger International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which covered the trade and technical groups – electricians, carpenters, engineers, lighting technicians.

The talent – writers, actors, directors – were not organised, and that, in fact, is how the annual Academy Awards came about. The Academy Awards were the creation of Irving Thalberg, the driving-force behind Metro Goldwyn Mayer. Thalberg wanted to emphasise the non-union character of the movie industry by creating an “Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences.” This would bring together, in body and soul, the executive producers who did the hiring and firing and the “esteemed actors, writers and directors” who were hired and fired.

As it still does today, the Academy honoured its members with dinners and annual affairs where it presented awards for the best films, best performances, best direction and best scripts and hailed the winners as “artists”. But its role back in the ’20s and ’30s was to function as a form of company union.

The stock explanation for the eventual arrival of the Screen Writers’ Guild is an intriguing twist on a very 20th century industrial phenomenon – technological change. The talkies arrived. And with the talkies, Hollywood producers needed writers adept at dialogue rather than titles. So they recruited playwrights, novelists and journalists from the literate cities, New York and Chicago. And these writers brought with them a strong union background.

They were writers like the wonderful Dorothy Parker who advised everyone, “Looking to the Academy for representation is like trying to get laid in your mother’s house. Somebody is always in the parlour, watching.” At a meeting where an inflated screenwriter put forward the view that creative writers didn’t need a union, it was Dorothy Parker to the fore again, shouting out, “If you’re a creative writer, I’m Queen Marie of fucking Rumania.”

But, ultimately, there were other factors in the unionisation of Hollywood besides wisecracking alcoholics.

First, and most obviously, the talent wasn’t dispersed or isolated. It was hired in bulk. (It’s no coincidence that the unionisation of scriptwriters in New Zealand occurred in the same year as the launch of our first TV soap opera.) Writers were placed in writers’ blocks where everyone could feel disgruntled collectively. Samuel Goldwyn was reputed to sneak round to the block at MGM and crouch under the window, just in case one of the dozen or so typewriters inside wasn’t clacking busily away. Studio writers recorded how Dorothy Parker once hurled herself at the window of the Paramount block and wailed to the world outside, “Please! Help us out of here! We’re sane, just like you!”

Second, there was the example of the wage cuts. In March 1933, Louis Mayer, “red-eyed and unshaven” – we have an eye-witness account here – summoned his employees and began to speak: “My friends, my friends…” He couldn’t continue. He broke down. Stricken, he held out his hands, supplicating, bereft of words. The worst had happened. Metro Goldwyn Mayer had run out of cash. It was the depression. There would have to be a 50% pay cut all round. As Mayer, in tears, left the meeting he was heard to whisper to an aide: “How did I go?”

Now while others took the cuts, the trades and technical union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, flatly refused, stood firm, and won the day. So you had this shining example. Writers, actors and directors saw that individual contracts didn’t mean a thing when you were dealing with the studios. You needed a collective backed with collective action.

Third factor, and it turned out to be a crucial one, was that an administration friendly to unions had just moved into Washington. This was of course the New Deal Roosevelt administration.

Thus, in 1933 writers – and, in fact, actors and directors, began resigning from the Academy and looking to themselves.

“Drink! Drink! Drink! Drink! Write your masterpiece! Till twenty thousand pages have been filled! They’ll all be thrown away But the producers have to pay The members of the Screen Writers’ Guild!”

But the producers wouldn’t pay. Attempts to negotiate with the producers and studios failed utterly. The bosses just didn’t want to know – of course.

The patient writers became fed up. Mild-mannered Dudley Nichols caused a major shock when, in 1936 he refused to accept an Oscar for Best Screenplay (The Informer) because of the Academy’s continuing attempts to stop a screenwriters’ guild being formed. (We shouldn’t shower him with too much praise; he later changed his mind.)

The Screen Writers’ Guild now hurled down the gauntlet. A vote was taken that all writers would refrain from signing contracts for any script work that would extend beyond a strike date set at May, 1938. The Guild also announced plans to join forces with the two east coast unions that represented writers. One big union, one big strike.

The studio heads struck back. First they embarked upon the usual red scare – that communists were running the Screen Writers’ Guild. Quite true. Second, they put the word around that an amalgamated writers’ union would see east coast big-shots pushing the west around.

But it was their third response that proved killingly effective. They set up and fostered their own union, a compliant company union, a yellow union, and favoured those who joined it with work. It was the Academy all over again and dealt a bitter, almost fatal, blow to those struggling to organise an independent, democratic writers’ union.

Let’s just pause here and take our attention off the writers, for a minute or two. It wasn’t just writers who’d moved west from New York and Chicago.

By 1936, possibly earlier, the leaders of the International Affiliation of Theatrical Stage Employees, the large trade and technical union that had so staunchly rebuffed the pay cuts of 1933, had begun taking kick-backs from the studios.

The studios claimed it wasn’t bribery, it was extortion. Whatever it was, it came in suitcases and these union leaders were now spending weekends in Chicago casinos where their large amounts of folding money attracted attention.

Before you could say “Al Capone” the International Affiliation of Theatrical Stage Employees became controlled by the Chicago mob.

The mobsters, of course, had been well aware of the fortunes being made in Hollywood and had already been financially active. Al Capone’s man in Los Angeles, Johnny Roselli, arranged for the East Coast gangster Longy Zwillman to provide the capital for producer Harry Cohn to take over Columbia Studios. Zwillman, in exchange, was handed Columbia’s platinum blonde star Jean Harlow. Arthur Rothstein, who fixed the 1919 World Series, was an early investor in the parent company of MGM. Mobster Frank Nitti, later to take a bullet in the head, gave boot-legger Joseph Kennedy, father of all the Kennedys, entry into the lucrative and sexy motion picture world. Things were going on, money was being made. But now the mobsters could invest their profits from booze and prostitution into the studios while at the same time ensuring labour peace through the mass union they ran.

In 1937, rumours began spreading that this corrupt International Affiliation of Theatrical Stage Employees had done a secret deal with the conservative American Federation of Labour to have jurisdiction over all the jobs in the film industry. This alarmed the writers. (It also alarmed the actors and directors).

At the same time the Roosevelt administration was pushing new labour legislation through the courts to give legal power to legitimate, representative unions.

From out of its coffin the Screen Writers’ Guild rose again, organising once more for a writers’ union independent of the studios and the Academy.

In June 1938, the National Labour Relations Board considered a petition from the stubborn remnants of the Screen Writers’ Guild and ruled that under new labour legislation screen writers could vote for the organisation they wished to represent them and that producers had to sit down and negotiate a contract with that organisation.

Writers began streaming out of the studios’ yellow union and into the Guild, “like shits leaving a sinking rat,” as the writer Dalton Trumbo eloquently put it. The Guild was victorious.

Concurrent with the unionisation of Hollywood was the growth of the left – each, of course, driving the other. The 1930s had witnessed the rise of fascism and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and both causes attracted campaigns and campaigners.

Dorothy Parker and Oscar Hammerstein II (who wrote the lyrics for the anti-racist musical South Pacific, as well as The King & I and The Sound of Music) founded the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. A Spanish Refugee Committee was established and Spain became known as “the writers’ war”.

The actress Karen Morley, who starred with Paul Muni in Scarface, said anyone who joined the progressive political movement in Hollywood rapidly became an alcoholic, because, “You would be drinking at one benefit on Friday night, another on Saturday and two on Sunday. You were smashed all the time.”

The alliance between communists and liberals grew enormously. Sympathetic to the left were James Cagney (who later helped fund the IRA), Edward G Robinson, Charlie Chaplin of course, the actress Frances Farmer, Dorothy Parker I’ve mentioned, the writers Dashiell Hammet and Lillian Hellman, Orson Welles, the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee (“Always ready to bare her navel for the commies”), the singer Lena Horne, the playwright Clifford Odets – author of the most celebrated play of the period Waiting For Lefty, Paul Robeson of course, Ronald Reagan (!), Katherine Hepburn, Groucho Marx, Bette Davis, Boris Karloff. The greatest American novelist of the 20th century, Scott Fitzgerald, who was working in Hollywood, applied to join the Communist Party but was rejected because of his drinking. (Does make you wonder how some of the others got in.)

The screenwriter Ring Lardner Jnr, who went on to win an Oscar for Woman of the Year and to write The Cincinatti Kid and M*A*S*H recalled, “Most of the people I came to know as communists were brighter and more admirable and more likeable than any other people. I once proposed the slogan, ‘The Most Beautiful Girls in Hollywood Belong to the Communist Party.’”

Of course there was very much a degree of radical chic to it all. Ring Lardner Jnr commented that Hollywood reds were probably the highest paid Communists outside of the Kremlin. There’s a story of writer-director Robert Rossen, who went on to write and direct the wonderful Paul Newman pool-hall movie The Hustler, cautiously wanting to know if Party dues would be based on income earned before or after tax.

In her marvellous book, The Hollywood Writers’ Wars, Nancy Schwartz writes that the Communist Party “suffused everything with meaning. If you got drunk, you did it for Spain…” and Schwartz makes the obvious point that the Party helped remove the guilt surrounding Hollywood’s enormous salaries, particularly during a time of mass unemployment.

But we should give Hollywood’s left-wing writers credit for more than just dialectical materialism by the pool. They took their craft seriously and questioned everything. They held workshops to discuss thorny topics like “the woman question” where they argued that female leads had to be seen as being more than just love-interest fodder. They began turning out crackling dialogue for Katherine Hepburn and gave women characters complex personalities. They avoided characterising blacks as shoe-shine boys and maids. In fact they did this to the extent that some black actors were rumoured to have begged them to stop as it was putting people out of work.

In a whole range of unions, but particularly in the Writers’ Guild, the left was in the ascendancy. Even in the corrupt International Affiliation of Theatrical Employees a reform movement was under way. Marvellous movies like The Grapes of Wrath were lighting up the cinema screens. Orson Welles, freed from studio constraints, was about to begin work on the greatest, freshest American movie ever, Citizen Kane. California was second only to New York in its numbers of communists, with a membership of close to 10,000, 46% of them women. An up-and-coming young actor, Ronald Reagan was telling meetings of the Screen Actors’ Guild that all creative artists must band together in the fight against fascism… What could possibly go wrong?

In 1939 the war everybody had been expecting broke out in Europe and by the end of 1941 the United States and the Soviet Union were both involved, as allies. Pro-Russian films started to be made at the behest of the studios. Go up to VideoEasy on Ponsonby Road and you can hire out the truly appalling piece of Stalinist fantasy The North Star, written by the playwright and screenwriter Lillian Hellman, about whom the Trotskyist writer Mary McCarthy once said, “Every word she ever wrote was a lie, including ‘the’”.

Warner Brothers invited the film critic of the Daily Worker to advise them on their own contribution to popular frontism, Mission to Moscow, in which Stalin was portrayed as everybody’s favourite uncle, a kindly gent much loved by his people, troubled by the Moscow Trials of the 1930s, though accepting that they were the only reasonable and just way of dealing with malcontents.

But there were worrying signs. Ring Lardner Jnr, like his fellow members in the American Communist Party, was a super-patriot during WWII, working on various propaganda projects for the U.S. war effort. Nevertheless he was listed by J Edgar Hoover’s paranoid Federal Bureau of Investigation as a “premature anti-fascist”, as the startling language of the time had it. When Dorothy Parker wanted to become a war correspondent, she couldn’t get a passport. She, too, was considered a premature anti-fascist.

Back in the real world, the studios and the producers really didn’t give a stuff about Moscow, one way or the other. They just wanted the unions smashed. That opportunity came in 1945.

After a brief attempt at reform, the big Hollywood trade and technicians union, the International Affiliation of Theatrical Stage Employees, was back in business, in the hands of the Mob. It was the union the studios liked to deal with. Raymond Chandler, writer of some of the best American hard-boiled private eye fiction and screenwriter of the classic Fred McMurray/Barbara Stanwyck Double Indemnity, once wrote to a friend that he’d just seen a band of studio executives trooping back from lunch. He said they looked “exactly like a bunch of top-flight Chicago gangsters.” He said it brought home to him in a flash “the strong psychological and spiritual kinship between the operations of big business and the rackets. Same way of dressing, same exaggerated leisure of movement.” (I once read how Claud Cockburn, the London Times’ correspondent in Washington in the early 1930s, interviewed Republican president Herbert Hoover and gangster Al Capone on successive days, then got his interview notes confused and couldn’t tell one from the other.)

Now, growing way to the left of the Theatrical Stage Employees was a new and significant rival, the Conference of Studio Unions. It had started off during the war as an amalgamation of five small craft unions that had escaped the embrace – or throttle – of the Theatrical Stage Employees and was founded in the wake of a successful strike of cartoonists at Disney Studios. By 1945 it had grown to 10,000 members. It stood for what the New Zealand waterside leader of 1951, Jock Barnes, used to call “bona fide unionism” and its leader, Herb Sorrell, was a lot like Barnes. Sorrell was an ex-boxer, belligerent, convinced of his rightness, a left-wing non-communist who believed in no retreat and took his own counsel. His union was seen by the Theatrical Stage Employees as a threat and by the studios as giving a militant lead to others.

In March 1945 a job-lot of Hollywood tradesmen voted to join Sorrell’s Conference of Studio Unions. The International Affiliation of Theatrical Stage Employees stepped in and claimed the tradesmen as being in its jurisdiction. The studios, waiting to have a go at the Conference of Studio Unions, and with nine months stock of new films on the shelves, backed the gangsters.

Sorrell called a strike. Now while class-conscious studio heads stood shoulder-to-shoulder against the common foe, the unions and the left were divided. Many didn’t think the strike was winnable. Others didn’t trust Sorrell. And America was still at war and the Communist Party supported a “no-strike” pledge to Roosevelt and the Soviet allies fighting the Great Patriotic War.

In the world outside of Los Angeles, other things were happening. In August, the war was brought to an end at Hiroshima. This released the Communist Party from its pledge, but another war, the Cold War, had been gathering and the studios took full advantage of it.

The Conference of Studio Unions was denounced as being in the pay of Moscow. The new president of the Screen Actors Guild, Ronald Reagan, who was being briefed by the FBI, renounced his liberal past and said he believed the Conference of Studio Unions was a communist front exerting the will of Moscow on Hollywood.

A stampede to the right began and the course of that movement took actors and writers and directors across picket lines. The studio heads did a deal with the corrupt Teamsters Union who nullified a vote to support the strike and instructed union members to carry busloads of strike-breakers through the picketers.

There were bombings and beatings. Newspapers and magazines, always ready for Hollywood sensation, ran front-page reports of studios encircled by chanting strikers. Cinemas were picketed. Groups picketing the new Deanne Durbin murder mystery Lady on a Train, starring Ralph Bellamy and David Bruce, shouted out to the queues waiting at the ticket box, “Ralph Bellamy did it. David Bruce gets the girl. Save your money.”

In October there was a climactic riot at Warner Brothers where hundreds of police and picketers fought a pitched battle. With seven months gone, both sides drew back and accepted arbitration. The strikers were reinstated, existing contracts respected and issues re-negotiated. But the seven months had exhausted the union and resulted in division on the left. Workers were facing court appearances and fines after mass arrests.

The producers now met with the Affiliation of Theatrical Stage Employees and came up with a strategy to finish off the CSU, the Conference of Studio Unions.

The following year the studios announced that Affiliation grips would henceforth have control over set erections. This was normally the job of CSU carpenters. The CSU said if the studios enforced the move, the union would black all set-building. The studios said, right, and locked out all CSU members.

The Conference of Studio Unions was doomed. There was a near-riot at MGM when 500 pickets confronted scabs. Fists, clubs, stones, bottles were used. Police cars were fire-bombed. Many CSU members wore their old army uniforms, some wearing battle ribbons. The police were brutal and were backed up by the courts. There were mass arrests, mass trials – and surely and steadily the CSU was dismembered and replaced with the hoodlum-run Affiliation.

This crushing of the Conference of Studio Unions set the stage for the Hollywood witch-hunts, purges and blacklists that we are all familiar with.

In an atmosphere of increasingly rabid anti-communism, the Roosevelt New Deal Democrats were swept from Congress. Emerging as the new congressman for Orange County, California, was Richard Nixon, his campaign funds raised at dinners thrown by Mickey Cohen, the Los Angeles Mob leader.

The Hollywood left, after a decade of cheerful popular frontism, was totally confused. I remember seeing a TV programme about the actor Robert Michum, who had worked and sold The Daily Worker on the New York docks and was wised up to the ways of the bosses. He said he was shocked when he came to Hollywood just after the war and saw writers and directors and actors sitting around openly reading The Daily Worker. Didn’t they know the way things were heading?

The answer was, no. “Almost no one,” Ring Lardner noted, “had anticipated how quickly the tide would turn to rightist reaction and a Cold War.” And it applied here in New Zealand. Peter Purdue of the old de-registered Carpenters’ Union talked about it in the documentary Shattered Dreams saying, “The Party never knew what hit them.”

The writers, who had started claiming ownership over their screenplays and all the rights that went with that, and who were calling for an end to the protectionist restrictions on the screening of European films in American cinemas and for a free intellectual exchange of ideas, went down in a heap.

Reaction swept Hollywood, and the talent, with the brave exception of a few, went with it, fearing the loss of affluence and popularity. And fearing jail sentences.

By 1947 the House Committee on Un-American Activities was in session, interrogating suspect reds and listening to that intellectual heroine of Lindsay Perigo and Deborah Coddington, the loopy Russian-born Ayn Rand, testifying that she had never once seen a smiling child in the Soviet Union from the time of the Revolution in 1917 until her departure in 1926.

The writer Dashiell Hammet was dragged before the Committee and sentenced to a year’s hard labour after he refused to name the contributors to a Civil Rights bail fund he’d put his name to. He later confessed to friends that he didn’t actually know who any of the contributors were.

The internationally famous German Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht, now a Hollywood resident, was summonsed. He had the useful experience of having lived in Hitler’s Germany in the early 1930s. He was adamant he was not a communist. Asked if he’d ever applied to join the Communist Party he wailed, “No, no, no, no, no, never!” The committee thanked and congratulated him and said, “You are an example to the other witnesses.” The following day he packed his bags and fled for East Germany.

Clifford Odets, formerly the most famous left-wing playwright in America and now a Hollywood sceenplay writer, was summonsed. He told the Committee he had left the Communist Party because he didn’t like being told what to write. Veteran Hollywood writers fell over backwards, laughing.

Ring Lardner Jnr refused to cooperate with the Committee. He was jailed and in jail found there was curiosity and puzzlement about what crime he had actually committed. He recorded, “The inmates finally figured out it was some kind of refusal to talk to the cops. This met with general approval.”

In New York, at a public rally, a frightened Dorothy Parker spoke out in helpless anguish, “For heaven’s sake, children, fascism isn’t coming – it’s here. It’s dreadful. Stop it!”

Over the border in Mexico, the indestructible Dalton Trumbo took up residence and became Hugo Butler, Ian Hunter and Robert Rich and won two Academy Awards. “Ian Hunter can’t be with us tonight.” “Robert Rich can’t be with us tonight”…

The witch-hunt against the left was not just restricted to the movie industry. Thousands of militant trade unionists lost their jobs. All union officials had to declare they were not communists or be kicked out of the union under the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. Workers employed by the government – like teachers and university lecturers – were sacked if they refused to sign loyalty oaths. The best unionists were purged from the Screen Writers’ Guild.

It’s always important to remember that the Cold War of the 1940s and early 1950s was not simply an ideological battle whose roots lay in the competing foreign policies of the Soviet Union and the US State Department. It was also a reaction by big business to gains that had been won by militant unions as they came out of a depression, and to the expectations of union members as they came out of a war. That was the case in Hollywood. And it was certainly the case here.

What is singular about Hollywood in this period has been summed up by one historian in a brilliant illumination. Hollywood was the fulcrum, the see-saw of the central metaphor for postwar United States: the rise of organised crime and the decline of the organised left.

___________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

Hollywood Writers’ Wars Nancy Schwartz

Class Struggle in Hollywood 1930-1950 Gerald Horne

I’d Hate Myself in the Morning Ring Lardner Jnr

Writers in Hollywood 1915-1951 Ian Hamilton

Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell is This? Marion Meade

Post a Comment